Science writing: engaging readers without compromising accuracy

A scientist’s or engineer’s motivation for research and technology runs the gamut: Most of them can easily describe their work with equations, and they find a sense of satisfaction in numbers, comfortably immersed in data. But, when they surface for air, it’s still there: that driving burn to know — the nugget of insatiable curiosity that prompted them to ask questions in the first place.

The best science communication sieves through the jargon and clamps onto this drive and those questions. Curiosity unites us, and we can use this primordial spark to reach to anyone. A science writer’s or technology marketer’s job is to speak to people with different interests, comfort zones, and proclivities without misrepresenting the research.

In negotiating the space between the researcher and non-experts, we look to engage the reader without compromising accuracy.

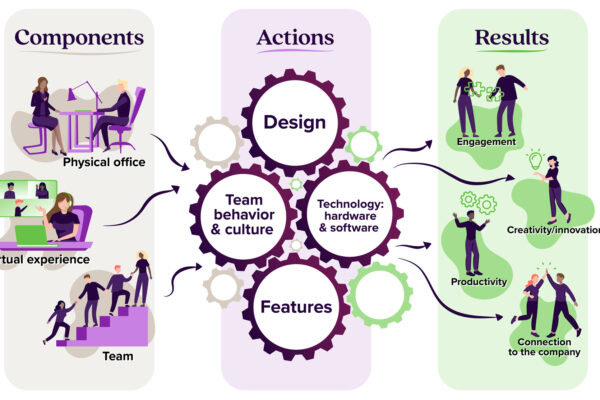

Engagement

If you demonstrate how the technology affects people, their daily lives, or their bottom line, you can get many to sit up and listen to stories that are way beyond their own expertise.

For instance, most Americans know someone (or is someone) who battles infertility. A researcher in the electrical and computer engineering department at Virginia Tech hopes to improve success rates of in vitro fertilization by creating better imaging technology.

It would be easy to get lot in the weeds on this one, describing the equipment, the computer models, the algorithms. And while those details are important, it’s also important to understand that the story’s hook is hope. It’s not a marketing ploy (although it makes good marketing sense to use it). People truly care about this issue, and the researcher is dedicating his life to easing the burden of infertility. Don’t bury that.

In most cases, however, your message will depend on your audience.

Audience

Who are you writing for? Engineers? Buyers? Politicians? The media?

Tailor your message to the people you are trying to engage. It will make it easier for them to listen, absorb, and act on your message. Nothing turns away a reader faster than long sentences full of unfamiliar jargon.

There is a time and a place for technical language. When a physicist publishes an article in a peer-reviewed journal that expands the boundaries of their specific research area, they don’t want to spell out the basics of electromagnetism because their pool of readers all took that class years ago. Here, the jargon saves time.

But even scientists who share the same field won’t share the same vocabulary — the deeper into a subject you dive, the more specialized the language becomes. And vice-versa.

A tip: If you have two words that mean the same thing, use the simpler one. That way no one will confuse your scientific prowess with showing off.

Accuracy

Beware click-bait-y science sensationalism. It’s not only irritating to experts, but it also hurts your credibility.

“What is reprehensible is the needless sensationalism and fear-mongering in journalistic communication of scientific results, achieved by sacrificing scientific accuracy and over-hyping incomplete parts of results – thereby misleading the general public and guiding their understanding of the research into a specific direction,” –Kausik Datta, Senior Research Specialist at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine

By the same token, communicators and marketers need to understand how science works in order to separate real breakthroughs from hype. John Bohannon, a science journalist with a Ph.D. molecular biology, carried out an elaborate hoax to expose just how easily bad science gets disseminated in the mainstream media. In May 2016, Comedian and political commentator John Oliver’s show Last Week Tonight focused on why media outlets so often report untrue or incomplete information as science. Like a game of telephone, he said, the facts get more distorted with every step.

We try to move away from the ponderous, stilted language so often found in academia and scientific journals because we think that the work is important, and we know other people will find it interesting – but we have responsibility to preserve the integrity of the research.

Striking a a balance between these priorities keeps it challenging.